Development and Displacement Down the Bay

Posted on May 21, 2024 by Rachel Hines

Down the Bay, the neighborhood south of Government Street in Mobile, is home to many notable figures – Civil Rights leader John L. LeFlore was born Down the Bay, as were four of Mobile’s biggest baseball legends. The Mobile Beacon, Alabama’s longest-running Black newspaper when it closed in 2018, was published Down the Bay, and St. Martin de Porres, the first Black hospital in Mobile, was located there too. Yet many Mobilians have never heard of the neighborhood.

Down the Bay sprung up in the late 1800s and grew into a thriving interracial neighborhood. Though it still exists today, it was completely transformed by development in the 1960s and 1970s, erasing historic businesses and homes from the landscape and forcing many residents to relocate to other parts of Mobile. These development projects follow a pattern seen throughout our country; in the 1950s and 1960s, our federal and state governments built interstates through Black and other minority neighborhoods. City-led urban renewal projects followed, leading to the demolition of entire blocks of housing.

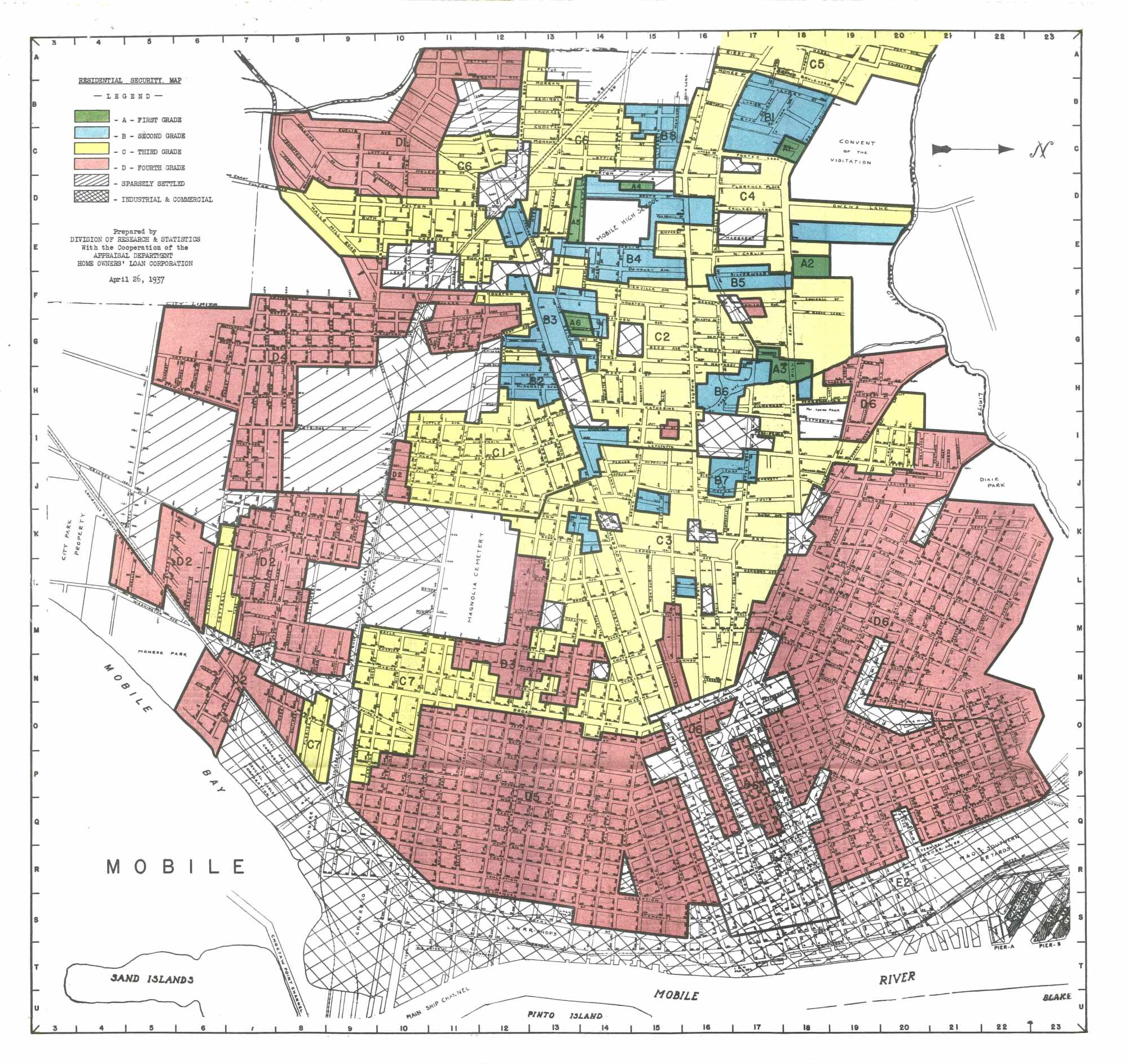

Early planning for these projects can be found in “redlining” maps, which were created in the 1930s by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal agency. These maps graded residential neighborhoods on their “security.” “Hazardous” neighborhoods were marked red, often due to the presence of African American, immigrant, or Jewish residents, which HOLC considered a threat to home values. These policies led to discriminatory loan practices and disinvestment in these neighborhoods. In the 1937 redlining map of Mobile (below), Down the Bay is almost completely red. Despite this, the neighborhood is described by HOLC as having “Good churches, schools, community business center and recreational parks. Good transportation facilities.”

1937 map of Mobile showing the “residential security” of neighborhoods created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a federal agency. Interact with the map online through the University of Richmond’s Mapping Inequality project.

Redlining set the stage for interstate construction and urban renewal projects, which occurred in neighborhoods deemed “hazardous.” In the early 1960s, the State of Alabama began purchasing properties Down the Bay to build Interstate 10. Initial planning documents proposed a route down St. Emanuel Street; however, the road was moved west to run between Claiborne and South Conception Streets along the route of Our Alley, a crowded alley with cheap rental housing. The construction of the Interstate forcibly relocated about 2500 people from 500 households and isolated the area east of the Interstate from the rest of the neighborhood. Today, that area is completely industrial.

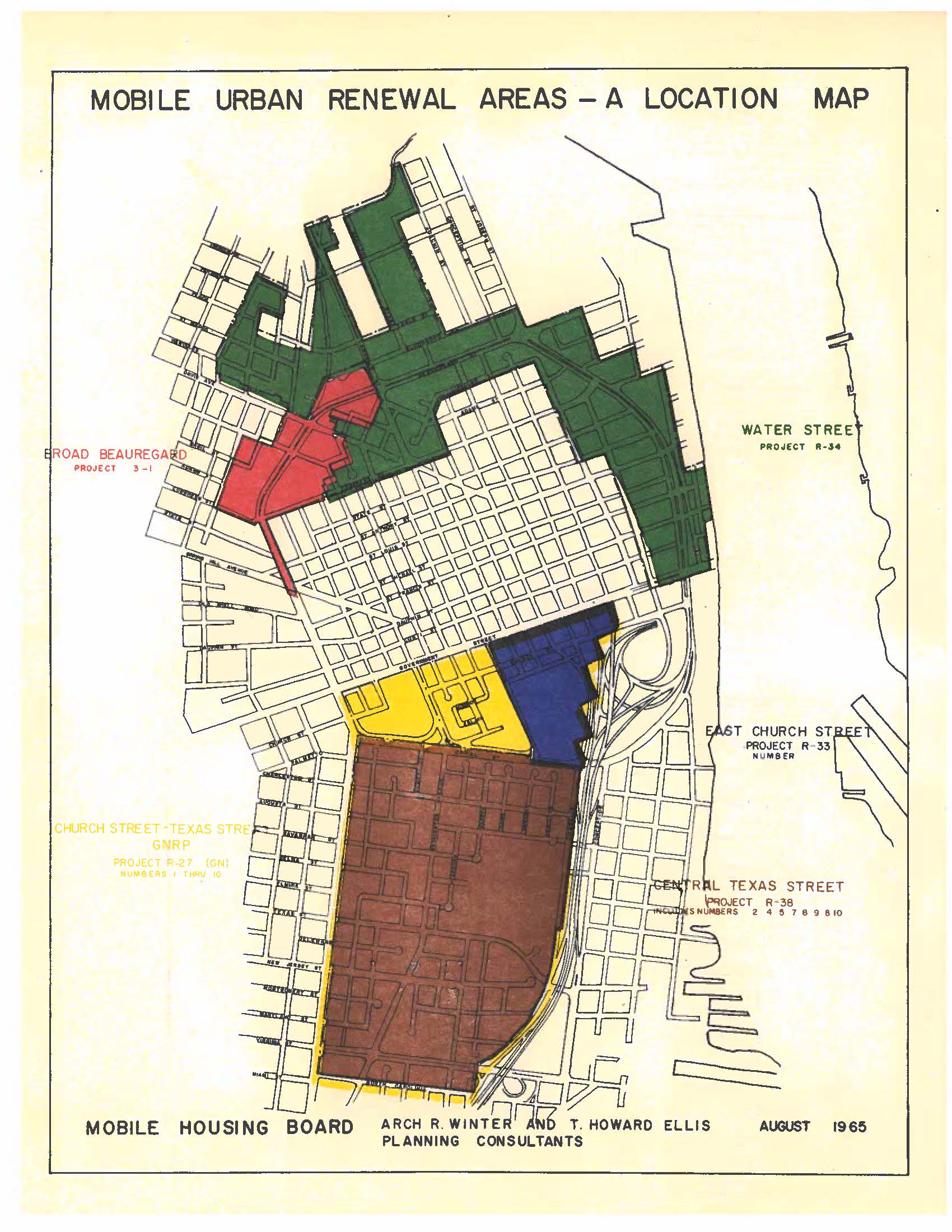

1965 Mobile Housing Board plans for urban renewal projects. Courtesy of Mobile Housing Board Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

At the same time, cities across the United States razed entire blocks of housing for urban renewal projects. These projects aimed to remove “blighted” properties from the landscape to redevelop and modernize cities. Instead, they resulted in the destruction of minority and low-income communities and displacement of residents and businesses. In Mobile, this process was under the purview of the Mobile Housing Board, whose records are on file at the Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library on campus. In addition to maps and plans for the neighborhoods, these records include appraisals of each house purchased for the projects, including photos, floor plans, and the value of the property.

The largest residential urban renewal project in Mobile was the Central Texas Street Project, which encompassed much of Down the Bay. Nearly 2,000 households were purchased through eminent domain, forcing thousands of residents to relocate. The Interstate seems to have directly influenced plans for this project; a 1967 Mobile Register article quoted a city commissioner who was concerned about the neighborhood’s appearance:

“Central Texas Street lies off the beaten path and a majority of citizens scarcely realize the conditions that exist there. But soon it will be exposed to the view of millions passing over Interstate Highway 10 every year. It will be the gateway to Mobile and visitors passing through it will wonder how Mobile ever became known as the city beautiful. We simply cannot let it be exposed to the view of tourists and others. It must be rehabilitated.” (as quoted in Johnston 2022).

1960 aerial photo of Mobile showing the impacts of government development projects Down the Bay in the 1960s and 1970s. Aerial image courtesy of Geography Department, The University of Alabama.

These government-sponsored development projects Down the Bay relocated over 2500 households in the span of a decade, completely changing the neighborhood. Though Down the Bay remains a residential area today, it lost both the business district and the community’s connectedness, as former resident Marjorie Kenny Jones remembers in her 2022 interview for the Down the Bay Oral History Project:

“The Down the Bay community within itself was a city; we had everything. It was a community that, everybody knew everybody. That was your family. I didn't have too much of a family growing up, but Down the Bay. And that's why, when it was taken away from us and we were displaced like we were displaced, we lost a lot. We lost that connectivity that we had. We lost that community feel, that safe and secure feeling that we had with Down the Bay.”

Recently, the City of Mobile released a Resilience Assessment to prepare for future challenges based on historical events and current concerns. The report includes a recognition of the legacies of redlining in Mobile, stating: “the acknowledgement and acceptance of these historic inequities and their present-day impacts is a necessary, critical step toward a truly resilient Mobile.” Down the Bay has proved to be a resilient neighborhood, but acknowledging the impacts of redlining, Interstate construction, and urban renewal projects is the first step in rectifying the damage done to the community.

Further Reading:

- Learn more about urban renewal in Mobile in Meredith Johnston’s 2022 article “Urban Renewal in Mobile, Alabama: The Central Texas Street Project, 1963–1974”

- Learn more about our national history of development and displacement in “Urban Renewal” from the Inclusive Historian’s Handbook and from Segregation by Design: An atlas of redlining, “urban renewal,” and environmental racism

- Learn more about how other cities are tackling the legacies of interstates and urban renewal in “What It Looks Like to Reconnect Black Communities Torn Apart by Highways” from Bloomberg